A Closer Look at the Incumbency Advantage

By Miroslav Bergam

October 2, 2020

Introduction

Being the incumbent candidate in a presidential election – whether that means running for a second term or serving as the candidate for the party that previously held office – comes with a host of unique implications. Do the sum of these factors end up hurting the incumbent? Or do they offer an advantage?

The most obvious advantage for incumbent candidates is familiarity. The entire country is already familiar with the incumbent candidate, as the four-year media advantage offers nearly universal name recognition. If the candidate is a member of the incumbent party rather than being the direct incumbent, there are similar benefits. The country is already acclimated to and familiar with that party’s policies, and that candidate is likely endorsed by the previous president, who has the aforementioned name recognition.

How the incumbent party uses their power in office can also lead to an election advantage. One eyebrow-raising tactic is the strategic allocation of federal grant money, also known as “pork”. By funneling federal aid to states in the election year, perhaps even targeting states that could swing for one candidate or another, the incumbent party could sway the electorate in their favor.

There are also some clear disadvantages to being the incumbent or of the incumbent party. One disadvantage is accountability: the incumbent party could be assigned blame for negative changes that transpired during their time office. These changes could be the fault of poor leadership in office, but they can also be factors that are out of anyone’s control, such as an unforeseen recession or public health crisis. Political polarization may also diminish the benefits of being an incumbent: in states that consistently vote for the same party election after election, incumbency may be far less consequential. For this reason, it will be interesting to investigate the incumbency advantage in swing states, who adhere less strongly to a specific party.

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Before we model incumbency, we can perform some exploratory data analysis to help us decide what to include in our model.

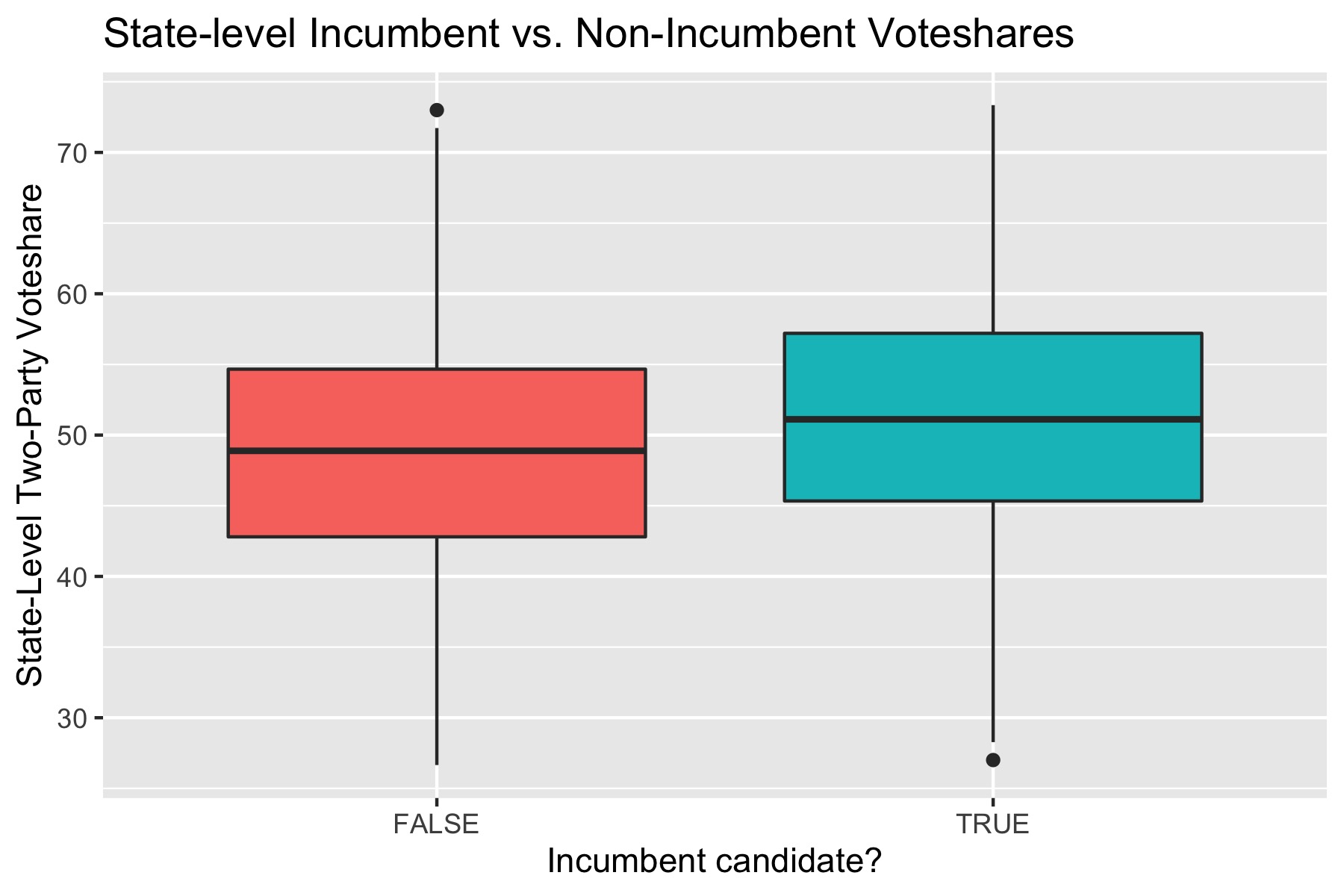

Incumbent candidates or candidates of the incumbent party have a higher average voteshare at the state-level in presidential elections. It’s worth taking a closer look at some other variables to determine how strong this advantage is and under what conditions it holds true.

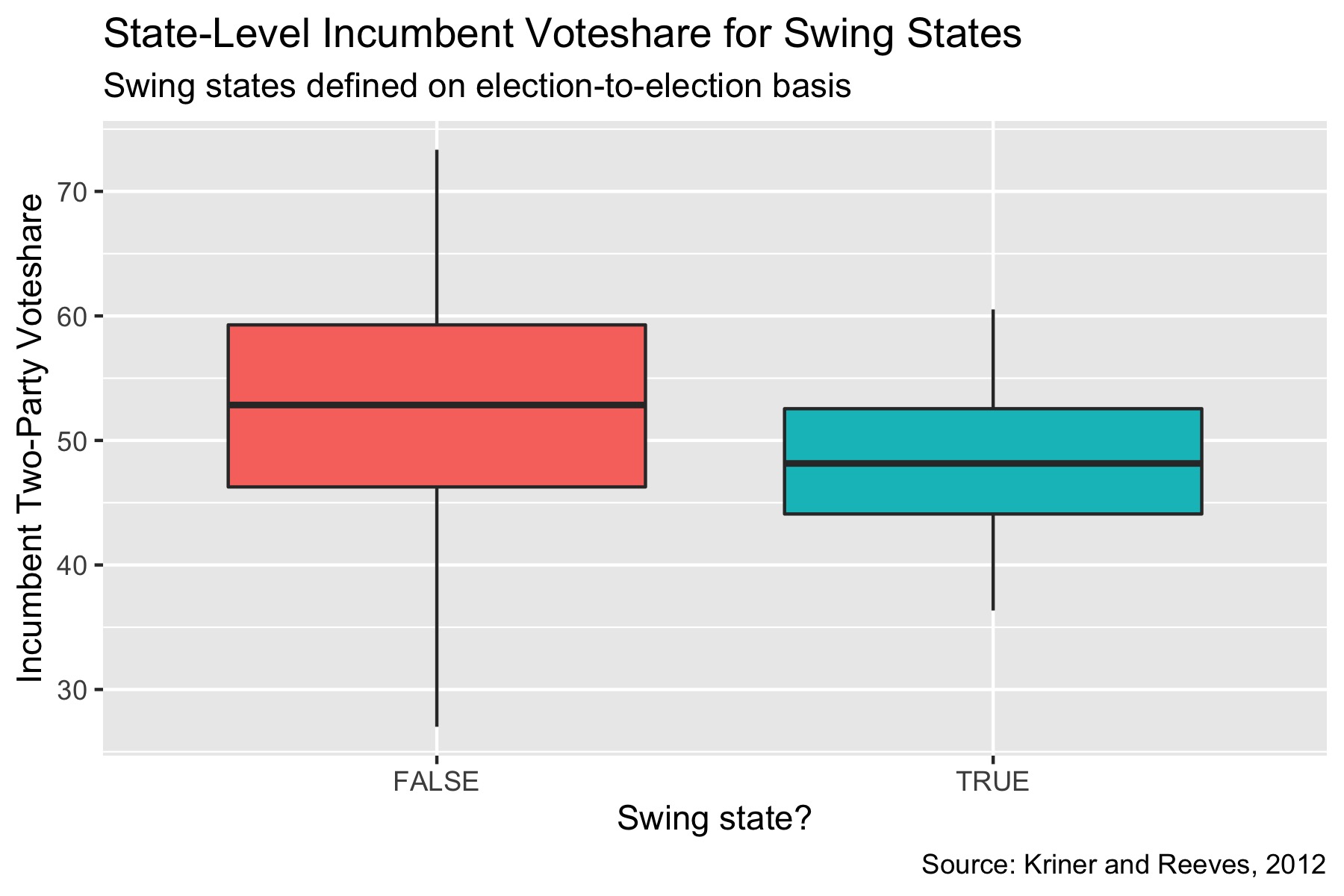

According to this graph, the benefits of incumbency vary across swing states and non-swing states. For presidential elections since 1984, incumbents have a lessened advantage in swing states. The mean incumbent voteshare in non-swing states is higher than the mean incumbent voteshare in swing states, and is about equal to the 75th percentile incumbent voteshare in swing states. The range is also wider for non-swing states, which is likely due there being fewer swing states. This trend is perhaps intuitive: because the winning party in swing states changes from election to election, swing state voters may care slightly less about which party holds the title of incumbent. It is worth noting that swing states in this dataset are defined by which states were regarded as swing states for each respective election, rather than a singular list being applied across all elections.

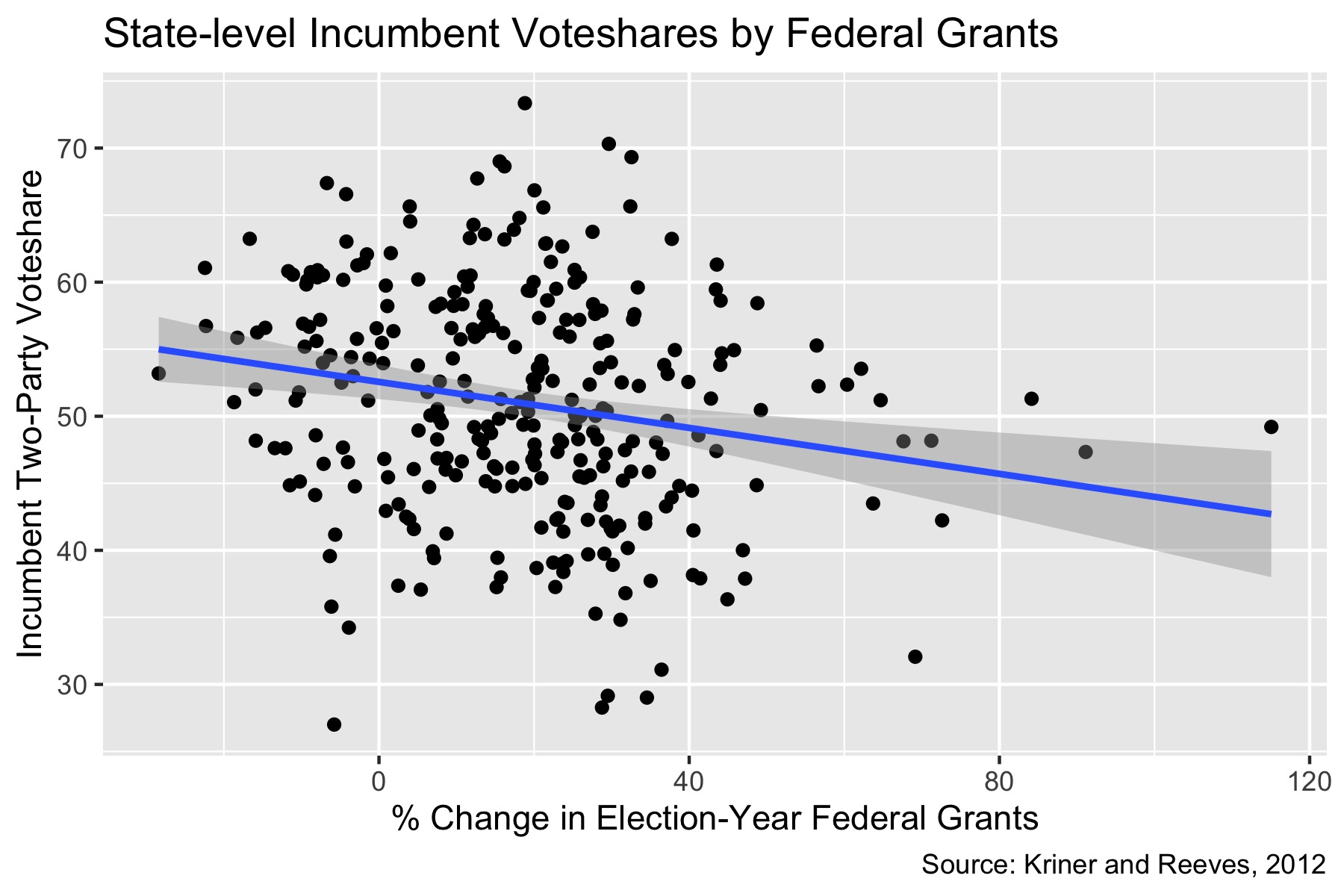

Pork, as we defined it earlier, seems to have a negligible effect on the incumbent voteshare, at least at the state level. Overall, there is a negative correlation, but it appears to be quite weak based on the spread of the datapoints.

Modeling Incumbency

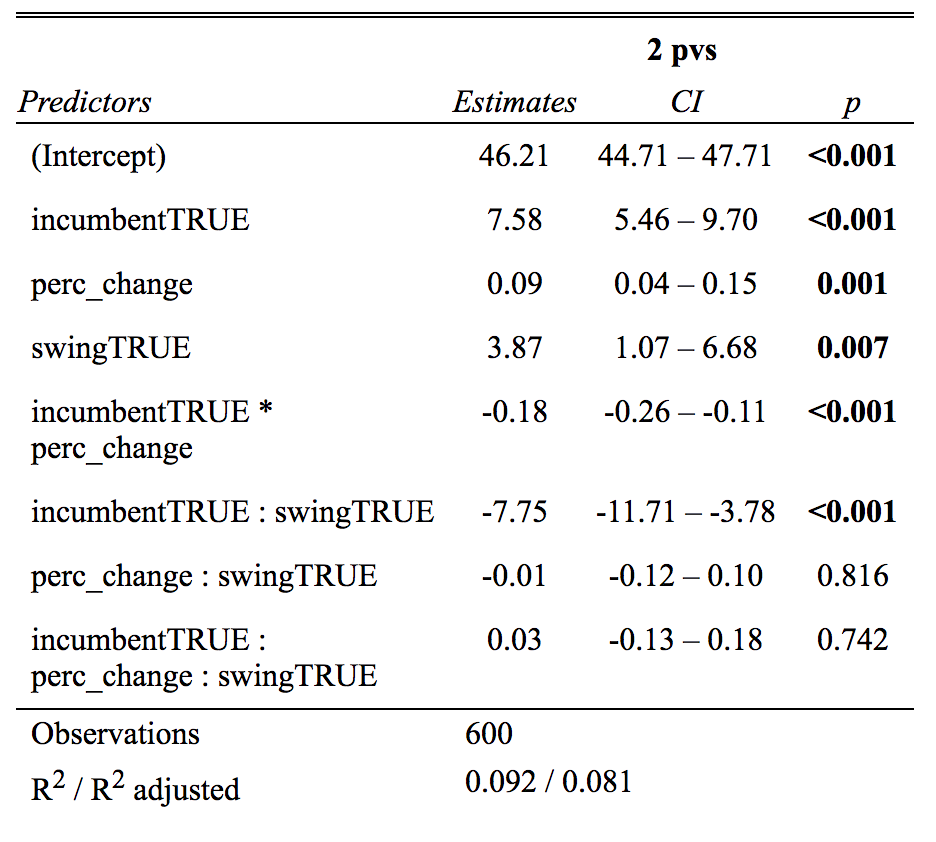

Given the findings of our EDA, I decided to model party incumbency (incumbent), swing state (swing), and percentage change in pork from the previous election year (perc_change) against two-party voteshare at the state level (2pvs), as well as the interactions between these variables. I used percentage change in pork rather than the raw amount of pork because that would not work on a consistent scale across states due to varying state population sizes. Overall, the model has a weak R-squared just shy of 0.1.

Controlling for the other two variables, there is a significant (p < 0.001) positive correlation of 7.58 percentage points associated with being a member of the incumbent party. The interaction between incumbency and swing is significant and negative, with incumbency associated with a 7.75% percentage decrease in the two-party voteshare in swing states. Finally, the change in pork from election to election doesn’t seem to have a substantial impact on election outcomes, with a small coefficient of 0.09 (controlling for other variables) and a small, non-intuitive negative correlation of -0.18 when interacted with incumbency.

Conclusion

The findings of our model are overall consistent with what we learned from our EDA. There is a measurable advantage to being a member of the incumbent party; this advantage is diminished in swing states due to their lack of allegiance to a singular party in any given election. Additionally, pork doesn’t noticeably impact election outcomes. This is likely because most voters aren’t aware of federal grant money being funneled into their state. Using federal grants and voting data at the county level may better represent the impact of pork, as voters are more likely to experience the direct effects of federal grant money at that level.

So, does incumbency yield an advantage? Yes, however the exact mechanism by which it does would require a broader and more finely-tuned selection of independent variables. In non-swing states, it appears that at least the status and name recognition of incumbency (rather than the allocation of federal money) benefits that candidate in the election.